Scott Johnston: Shoe Designer

Interview by Peter Wenker

VP: Based on prior interviews, it seems like you were first bitten by the design bug during your Mad Circle days and your proximity to Justin Girard’s creative process. Can you describe how that design bug creeped into your mind?

SJ: Well, at Mad Circle, when Justin Girard got his Apple computer he was able to work on the brand from his house rather than in a building under the same roof as other brands. That made him and the brand more approachable by leaps and bounds. I think before I was even officially on the team he would tell me “Scott, you’ve got to come over and see what we’re making.”

Plus, he’d explain it all with so much excitement while we’d be looking over his shoulder at the screen at every little detail and sticker graphic. I think it was Justin’s excitement for making things himself and making things that you care about that really stuck with me early on. Of course, at the time, I didn’t really react to that other than “Oh wow, that’s super sick,” because I was just so focused on only skating. But yeah, Justin was the first person to ever tell me that as you get older you should try to explore other interests while you have the time. It was great advice.

That certainly sounds like wise advice, especially considering this was a time in skateboarding when it was completely acceptable, and even expected, that as a professional skateboarder your only interest was supposed to be skateboarding.

For Justin to actually encourage me to not go out and always do what he was paying me to do—skateboard—was a good thing to hear. I wish I would have taken more advantage of his advice back then, because as a professional skateboarder you just have so much free time and your body can only handle so much for so long.

Our interview subject in an ad for the DC Plug. Via Vert Is Dead

How did your interest in design carry you through your time skating for DC Shoes?

At the time, DC was a new company and they were looking to do things differently. Back then, any other shoe company like Duffs or Etnies would give its skaters a couple pairs of shoes, and that was sponsorship. No one had the mindset that skate shoes needed to look like sneakers and have some of the spirit of sneakers—meaning looking nice and new and encouraging people that see you skate in them to want to go out and buy them. A pair of shredded shoes is not going to inspire anyone to go buy them. You’re not going to sell the dream in beat up shoes.

So, DC would send its skaters tons of shoes, you would never have to skate them to the ground. DC understood the importance of footwear being something more than just the thing between your feet and the griptape. The shoes need to look good. It was another lesson for me in the importance of footwear in skateboarding.

DC was also pushing the boundaries of technical skate shoes and pushing the importance of looking good in the shoes—I mean, they created the unified look for the DC Super Tour.

How’d it feel to be a part of what at least appeared to be one of the more “organized” teams in skateboarding? What other lessons did you learn from those DC days?

DC was introducing some new design elements to skate shoes. They weren’t satisfied just sticking some suede upper on a gum rubber bottom. I remember DC was paying attention to sneaker culture—like Nike Jordans and other designs using more progressive materials and layers. They would then try to emulate those outside influences into skate culture.

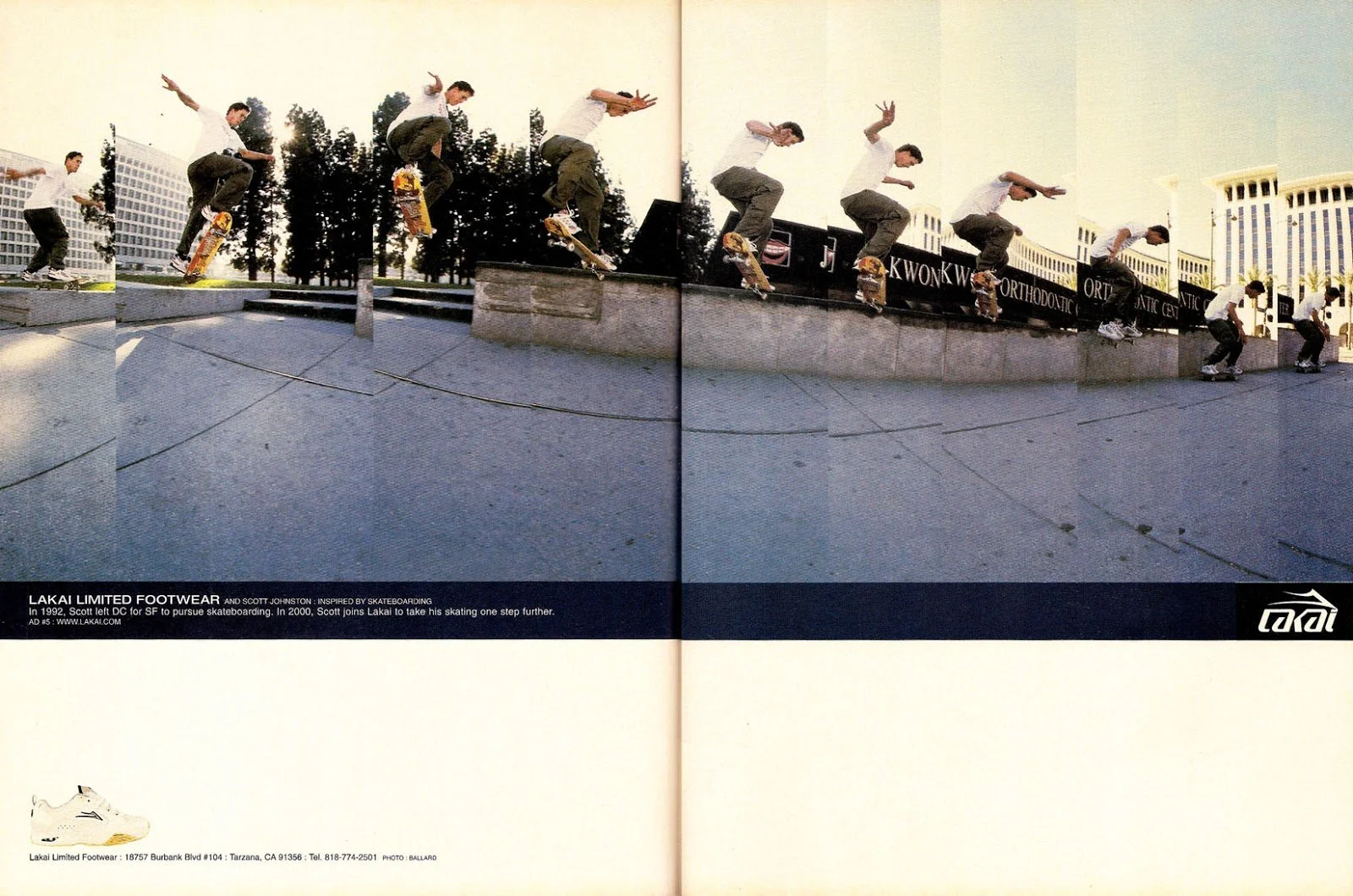

Early Lakai ad showing off the technical look the brand became known for. Via Vert Is Dead

I remember Lakai’s entry into skateboarding was through presenting those more technical design elements to skate shoes. You’ve previously mentioned in other interviews you wanted to transition from “skate accomplishments” to “design accomplishments”. How did the transition from skating in technical shoes to designing technical shoes at Lakai work?

I was there for the inception of Lakai, so it took me back to what we talked about at the beginning of this interview—being excited and caring about what you were making. At the very beginning, Mike Carroll, Rick Howard, and the first designer at Lakai Sung Choi would just go out shopping to research product and find shoes that could inform what sort of aesthetics they wanted for Lakai. I went out on those shopping trips with them, so that was my first interaction with what they wanted to do with Lakai.

Now, I didn’t make or inform any of those choices at first, but I was able to be there and observe Mike and Rick studying shoes to try and figure out the lane for Lakai. From that point on, I had a relationship with Sung, and at that time, Lakai was just down the street from Girl. So, if you went to go skate Girl, you could just stop down at Lakai to say what up, look at samples, and touch things. It was always just this natural ongoing conversation of looking at things with them and talking through designs or needs for the shoes.

And then, based on those conversations, I just started to draw stuff myself and give the drawings to them to show what I had been talking about. During that process, Sung would give me feedback and pointers. After Sung, then it was James Arizumi, who would let me get more and more involved in designing shoes that would eventually be made for me. It sounds magical to come from a place of having no formal design training to essentially apprenticing with the founders of a shoe brand and their designer, let alone being included in those initial shopping trips to just figure out what Lakai was going to be about.

Where did Rick and Mike take you shopping? Shoe stores?

We went to Barneys to look at high fashion stuff like Prada. They really wanted to look outside of skating for inspiration. While most skate brands were looking at the immediate periphery like Nike, Mike and Rick wanted to look elsewhere. From the start, Lakai wanted to look to fashion shoes. So, they’d go to Barneys and just buy shoes they liked in their sizes and take them home to study them on a desk.

It sounds like outro footage to a skate video—Mike, Rick, and Scott at Barneys buying shoes. I can just picture a sly smile on Rick’s face as he’s purchasing shoes to tear apart and study later.

(Laughs) Yeah, there was definitely a recon feel to those shopping trips.

This Scott Johnston Lakai pro model can be yours.

Did any of the initial Lakai designers have formal design training or education? Or was everyone there just learning together as they went?

Sung came over from DC and had worked at some early New York footwear brands. He did stuff for Stussy and Supreme in graphic design. Sung just had an incredible sense of style that he could translate to design. James Arizumi was next and definitely had a formal background in design.

After those guys, Aaron Hoover was the one who gave me the formal opportunity to design for Lakai when I wanted to transition out of skateboarding. He could see that my interest in the design aspect of things was growing and he just decided to give me an opportunity to explore that. He hired me as a junior designer and then just flooded me with things that I didn’t know how to do and left me to figure it all out, in the best way.

Scott learning to skate again. Kind of.

Was it still just a fun experiment at that point, or was there some real stress involved now that your design role was official?

It honestly felt just like learning to skate again. Every new trick or every new thing you do on the board, you’re learning. It works the same way with design. Every new task or problem they gave me helped me learn. It may not initially have been the most glamorous stuff, but it’s the foundational stuff that needs to get done—like a pattern revision or adjustment. I learned a lot of the little things that you don’t realize you need to know to be a shoe designer.

You often think it’s all high end concepts, but the bulk of it can be those back end details. Aaron definitely did a great job of pushing me into those spaces to learn the full spectrum of design.

In a prior interview with Lee Smith, you described how it kept you motivated to have a little success every day while designing. What did you mean by that phrase, a success every day?

I look at how skateboarding was then and compare it to how skateboarding is now. Back then, it wouldn’t matter if you put out an ad or put some footage out and then went completely quiet for a while because you’d often have to wait a year or so before your ad or footage was seen and enjoyed. The longer the gap would get between having your accomplishments get out there in a video or whatnot, the harder it would be to stay motivated. But in footwear design, for me, the little successes weren’t so reliant on other people seeing those accomplishments.

For design, it was just me sitting down at a computer and making a bunch of things happen “today” that weren’t dependent on other people, magazines, or videos. It felt good.

Design break from the skate session? Or skate break with some homework squeezed in?

At Lakai, what was your typical production schedule? How long would it take to see what you’ve worked on or designed hit the shelves?

At Lakai, it would normally take about twelve months to get from initial briefs to the shelves. But again, you feel successful way before it ever hits the market because you're excited that you’ve sketched this doodle, and then you have a review, and then it gets to a bigger place, and you're excited about all the colorways you’ve shown, and then you're excited about the CAD level design, and then you get samples coming back, and then you’re like “Yikes! This thing is a mess.” So, every little step of the way is a success, and you’re not worrying about it anymore when it finally hits the market. By then, you’re already over it and on to the next design. These days I really try to take time to appreciate it when the shoe hits the market and is advertised and celebrated. But, early on, I was definitely more like, “Nah, that wasn’t good enough. What’s next?”

To anyone who grew up skateboarding contemporaneously with Girl and Chocolate as those teams put out videos like Paco, Goldfish, Mouse, and the Chocolate Tour, it obviously looks like a dream (at least from the outside) to go from skating with your friends to then working at a skateboard company with them. In reality, what was it like having to pitch design ideas to Mike and Rick?

Looking back, it was so easy. I remember people possibly sitting on the floor, even stretching… design reviews were so casual, it really was an open conversation amongst friends. It was just us making what we wanted, how we wanted. With my position now, I’ve learned that I also do enjoy those additional layers and hurdles that come with working for a bigger brand. It may make me feel uncomfortable going into a room with people that have more traditional training than me, or come with a more professional way of speaking, but I like challenging myself to step up in this new space that as a skater, you can really otherwise shelter yourself from. I felt incredible fear when I first started considering leaving the floor or the couch with my buddies.

A star studded cast at Ty Evans’ wedding.

We kind of did the full journey all together at Girl, Chocolate, and Lakai—from watching TV together to going to each other’s weddings. To walk away from that was tough. To think about it more now, I see that making that created separation, but at the end of the day I feel like I’m still growing and learning, and I’m still feeling all the excitement we’ve been talking about during this interview. It’s rad. I do miss my friends though, big time!

Before we make the full transition from Lakai to adidas, can you describe what it was like to become a boss and a mentor when you brought Jeff Mikut into the fold at Lakai? You’ve talked about how people at Lakai made a great room for growth for you, so what was it like then having to be responsible for someone else’s growth as a designer?

Jeff was the first person I ever hired and he was a pure blessing. He was friends with folks in the Crail camp, so others could really put the “this guy’s legit” stamp on him. It was another example of building on friendship and that natural working relationship that those brands have been rooted in. Bringing Jeff on made me feel like I needed to be more of a responsible figure and more of a leader in the sense of steering the ship.

As young as he is, he’s an old soul, and he was so responsible and capable that I actually learned a ton from him. It turned out to be a great two way street where he pushed me to be a better designer and hopefully I pushed and challenged him too. He was the best dude.

In his prior interview with Village Psychic, Jeff described his role as coming in to take on the responsibilities of the day-to-day duties so that you could do more of the long term planning for Lakai. Was it a strange concept to start thinking long-term?

I love that he described it that way, because to me there was no actualized plan. Everything was so informal, so I’m glad he had that perception. (Laughs). I think by then I just had a little more understanding of the cadence of the process from design to release and the strategy behind actually releasing a shoe.

Do you have any fond memories of those initial technical designs at Lakai?

When I got there and started to design, the technical look they had was starting to shift to the vulcanized classic product. I loved the first Carroll shoe and the first Rick shoe, they were actually worlds apart from the puffy over designed shoes from other brands at that time.

Rick’s desert boot.

What was it like working with your friends when it came to designing them a shoe? For example, what was the design process like for that Rick Howard desert boot?

It probably just started with something quick from Rick like, “What if we designed something like a Clark boot?” From there, I’d have tons of freedom to run with those “instructions” and design something. More than often things moved quickly, once we got the concept down we went straight to sampling.”

That casual ease at Lakai was amazing. The other thing is that when you spend all your days with the people you are designing for, it may just come easier and more natural. You develop an intuition as to what person X, Y, or Z is into and would want in a design.

Jeff described the design process for The Griffin as being a form of parallel play for the same shoe. Was it hard to release the reins a bit and collaborate with someone new?

When you work with someone in design, you build trust and start to understand their process, and once you see their output, you become more confident in simply letting someone like Jeff just run with a project. Jeff definitely made it easy for me to hand it over to him. When I started thinking about Jeff’s growth I realized that I was actually in his way. We both needed a challenge and knew it was good for us both if I moved on.

What interested you about the opportunity to design shoes for adidas?

It was one of those things, where I felt like it’s a ‘now or never’ scenario and I just decided to make the leap. I just wanted to see if I could survive in an atmosphere that wasn’t built on my friendships, but on my abilities and drive as a designer. I wanted to know if I could make it on merit and output alone. Also, I knew that I would have to go to either Portland or Boston to be able to work for a bigger shoe brand. But I was just really interested in Portland and working for adidas. At the time, I saw adidas as the underdog with a really legit heritage in both classics and performance shoes.

How was the hiring process different at adidas? Did you feel comfortable relying on your hands-on experience at Lakai rather than a formal design education?

It helped being a skateboarder interviewing for a job in the skateboarding category, someone that knows the business and trend history. I later found out that when the position first opened up at adidas, the powers-that-be mentioned my name but decided not to hit me up because they thought I would never leave Lakai. But, just by chance, someone mentioned that I should reach out to adidas to inquire about the position. So, that cracked open that first door really fast, but then I still had to go through the entire interview process and pitch to a panel and then go on to interview with the V.P..

I enjoyed the process though, because it also gave me time to decide to see whether I really wanted the change.

What was in your interview portfolio?

I just brought in project based stuff. It wasn’t anything too elaborate. I probably just had a mood board that would show someone the what, where, and why as a one-pager. I’m sure I also peppered in some sketches and final product ads. I think it was basically a mix of everything I did. I also brought in a duffle bag of samples in various stages. I remember the interviewers being like, “Wait, what? You brought in physical shoes?” They were pretty surprised, but I think it helped for them to hold something in their hands while I was talking through my process.

Scott is qualified for any job he wants based on this alone. Via Vert Is Dead.

Since it was a skate category interview, did you go for the low-hanging-fruit and bring in any your own skate ads to remind them that, “Hey, remember I’m Scott Johnston. Want to see what I’ve done at JKwon”?

(Laughs). No, no.

Was there any culture shock moving from L.A. up to Portland?

Honestly, it was pretty tough. At first it seemed really exciting. We had a kindergartner and a third-grader at the time and they were all psyched at first, but once we realized we moved away from all of our friends, it got hard. We didn’t know the city well and we were trying to figure out the best neighborhoods and schools. It was tricky.

Do you find that your location affects your design? Is it easier to design somewhere like L.A. or New York where you are exposed to the day-to-day fashion of all the people around you, as opposed to somewhere like Portland with a smaller population?

Somewhat, but somewhere like adidas that has over 70 years of design heritage to look back on, you learn to really appreciate how to continue to build on that legacy. Within a month of getting there, my boss sent me to Germany to meet the V.P. of design, Nick Galloway. He shared with me his philosophy of design and how to tap into the brand. Walking through the adidas archive with him and a few other top adidas designers really gave me the understanding of the brand’s power and charm.

For the layperson, there seems to be a curtain hiding the skate shoe design process. One of my favorite videos, which is not readily available anymore, was the video of Dan Kinley and Dennis Busenitz pretending to be engaging in the design process of the first Busenitz Pro. It shows them looking through samples and picking colors, along with the famous Busenitz line “I like my shit boring.” What was it like tinkering with, at least in my opinion, one of the greatest skate shoes ever designed with the Busenitz Vintage and the Busenitz Indoor?

The Busenitz has such a wide range of design possibilities. Instead of making completely new shoes just we’ve just iterated on the classic, basically doubling down! From the one piece upper we did years ago and yes, the indoor shoe. It was fun to give his shoe a new outfit, put on some layering from the archive and play with a new tooling. I love the tooling on the indoor shoe.

What’s your process been like working with other adidas pros on their signature shoes?

Working with signature models in general, you have to adapt to the person you’re designing for. Tyshawn Jones was an awesome person to work with. When we first started the process, it seemed like no one was doing “pro shoes” anymore, so it was cool to start that back up again. At adidas, there’s this thing called Dream Week, where designers just come up with concepts and work with marketing on new ideas. I was talking with Jascha Muller from the sports marketing team and Andrew Sprigle from marketing about what working on a new pro shoe would look like in today’s atmosphere.

What would become the Tyshawn.

Jascha was convinced Tyshawn should have a shoe. They knew the work Tyshawn was doing and that his part in the Supreme video would catapult him into the limelight of skateboarding. So, I ran with it and developed a full dry run of what it would look like to develop a shoe for Tyshawn. I made a mood/inspiration board connecting the brand to Tyshawn’s persona and just the New York energy! I really tried in the pitch to convey the idea that he’s so much more than just a good skateboarder. My sketches were rooted in basketball, whereas Dennis’ shoe was rooted in soccer. It’s always cool to show how we can anchor a shoe in adidas’ history. We also brought in other designers to sketch about how this skate shoe could be rooted with basketball DNA. Everyone was all in at that point he just had to tell TJ.

Jascha flew Tyshawn up to adidas HQ and we sat him down to reveal this mood board and loose general concept. He had this easy smile and said “Cool…” or something like that. A few months later we flew to New York. We sketched in the Brooklyn office, and he would come in each day to check the process. We really workshopped it to give him as many options as we could.

Brainstorming with TJ and Clark Kent.

DJ Clark Kent happened to be in there a few of the days. His big thing he’d say was “You’ve got to be able to wear these with jeans!” It was such an awesome design process. Another ambition was to bring him along for the complete journey of building a shoe. Tyshawn came to the factory in Vietnam, saw the process and tested his shoe on site.

At any point in this process, did you have to sit down with any “suits” outside of the skate program to explain the significance of “pro shoes” in skateboarding?

No, not at all actually!

Do you ever feel like the other categories look down at the skateboarding category as “lesser than”? What are those relationships and/or interactions like at adidas?

It’s funny, because I would’ve thought that is how we would have been treated, but honestly, the other categories treat skateboarding with the utmost respect and appreciation. When we’re in reviews with other categories they are always excited to see what skateboarding has. They seem to appreciate how well we know our world and how far we push it to be just right. The brand really appreciates skateboarding.

Prototype of the pro model for some small surf town French guy.

What about Luas Puig? When you think about it, Tyshawn seems like an easier “sell” than some French guy who lives in a small French surfing town. How'd you explain to someone outside of skateboarding that Puig is one of the best to ever do it and needs to have a shoe?

It’s actually very similar because it goes beyond just him and his abilities on the board. The way we pitched Puig was leveraging his relationship with Palace. Palace is one of adidas’ biggest partners. It was sick because Gareth Skewis and Lev Tanju from Palace were probably equally as involved in designing the shoe as Lucas.

They all flew into Portland with Palace’s product manager, and we were able to get something together in like two and a half days. Well, at least a solid direction.

Dialing in the Puig with said small town French surfer and Gareth Skewis and Lev Tanju of Palace.

I enjoyed that process big time. They know their shit. Lev had so much energy and would have ideas to get me going. Lucas was pretty clear with the general approach to the shoe and Gareth really empowered me to go. We met a bunch in person to review the samples as things unfolded. But it wasn’t in a formal conference room or something, just casual in the hotel room while having beers or whatever.

And you then made a vulcanized version of the Puig shoe?

(Laughs) Yeah, I mean, Lucas really likes to skate in a shoe that is super low to the ground so he can feel like he’s barefoot. So the intent was to create something lower and simplified compared to the Puig — almost as if we went back in time to design the vintage model his shoe was inspired by.

Going back to your mentioning the vast adidas archives, do you ever feel overwhelmed by the seemingly endless well of shoe designs to draw from?

When you first get to the archives, they seat you in a dedicated lobby and an adidas historian talks to you about the history of the brand. It gives you context to understand that you aren’t about to just look at a bunch of samples sitting in a room. You have to wear white gloves so the oils from your hands don’t destroy the old materials. They’ll ask you what you want to see because there isn’t time to look at everything.

The first time I was there with the V.P., we were just trying to figure out what the future of adidas skate shoes would look like—which resulted in that adidas 3ST line of shoes where we focused on certain design aspects. I think what I’ve learned most from the archives is that you don’t need to use every trick on one shoe.

It’s crazy because adidas also has a digital archive and every once in a while someone will send me an archive shoe where I’m like, “All we need to do is remake this shoe one-for-one.” But you can’t grow doing that.