Jeff Mikut Designed Your Shoes

Jeff and the New Balance 1010, AKA the Tiago Lemos pro model. Photo by Jake Darwen

You may not know the name Jeff Mikut, but you should! There’s a good chance that you’ve skated shoes he’s designed while working for Vans, Lakai, and New Balance Numeric. Most importantly, he’s the real deal. His love for skating and what skaters appreciate in a product truly comes through in his work.

So here’s an interview with Jeff.

Interview by Peter Wenker for Village Psychic

Village Psychic: Let's start from the beginning. How did your interest in skateboarding transition into designing shoes for skateboarding?

Jeff Mikut: I grew up in Ohio and had a crew of friends that would skate and film all the time. With that came the desire to learn more about how to make a video and how to use video editing programs, which then led to learning what type of computer and software to use. Like most things in skateboarding, you want to try to recreate what you’ve seen other people do and then make it your own.

So, we spent a lot of time nerding out on songs, titles, and effects. This was before Adobe and those types of programs, so we used a lot of the generic software that would come with the camera. I think a lot of my design interest came from the desire to create something out of all our raw skate clips.

I always wanted to have a 'skate website'. So, I had to learn how to make one, and that became my main direction in school. We built a website, gave it a name and edited footage of all our friends – I was lucky to have a constant flow of content to filter through all the various video software. So, for me, the transition of my interest in skateboarding to design was always the desire to create skate videos and then have a platform to display it on.

We have no idea how Jeff pulled off a nollie heelflip backside lipslide on this contraption of a ramp, but then again, we have no idea how to actually design a shoe.

VP: What year or years are we talking about?

J: Our first video was hilariously called Baller Status. It was a VCD. We weren’t even making DVDs...it was like a CODEC version of a CD. It was 8 minutes long and all our graphics were made in MS Paint. I was 14, so that would have been 20 some years ago--around 1999, early 2000s.

VP: It would seem a designer who also skates would provide a certain level of integrity--as in, you can design what a team rider wants.

J: Totally. There’s a lot of aesthetic-driven design, but there are certain core elements that a skateboarding shoe needs to have. You can have the coolest looking shoe, but if it falls apart when you skate it or it’s not comfortable in specific areas of the shoe, it’s a miss.

VP: So being a skate rat helps?

J: When you start a project with a team rider, it is so important to have an understanding of the nuances of why a shoe skates well. A lot of times when I'm designing for one of the team guys, we’ll go skate together, especially during the prototype phase of the process.

Getting first-hand experience allows me to add certain design elements to the shoe that they may not have even asked for, but it compliments their style of skating. Certain skaters are more into fashion and design, so they bring a lot more direction to the project, and some just want a very utilitarian product, so it all varies. My goal is for the team rider to have that base level of confidence so that I know what they're into and can understand their respective needs. I can't relate to skating a shoulder height ledge or a giant handrail, but I can help boil the request down and then communicate that need to someone at the factory.

Jeff providing an illustrated example of how we ruin our shoes.

VP: In your experience do the factory representatives even know what their shoes are being used for? Do they know that one of the fundamental uses of the shoes they make is to be destroyed?

J: I’d imagine this varies, but in my experience, they don’t. Not unless you show them.

When we were in a factory in Indonesia they had no idea why we were ripping through their shoes so fast and why there were photos with holes in the shoes. They were like, "Why are people dragging their shoes on the ground?" They knew they were ‘skateboard shoes’ but were still really confused at the time. So, I had my board with me and had them watch me ollie a picnic table (somehow there was a mini table right there). They all got their phones out and filmed me in slow motion so they could see how a skateboarder uses their shoe to drag across what is essentially sandpaper and level the board out. It was such a cool moment, seeing the excitement once they all understood. It all clicked.

VP: How do you explain skateboarding to someone at a factory who has never seen the actual act of skateboarding?

J: I explain that kids are looking to have their shoes last for weeks to months depending on the level of skating. One thing we try to focus on at New Balance is having a high integrity of 'build'. When you go into it, you must explain to the factory that the shoes they are making are going to be used at a much higher caliber than, say, a typical fashion shoe that will just be walked around in or worn to school or what not. Also, it’s not common to use regular shoes repeatedly against sandpaper.

Rubbing one’s shoes against sandpaper is not common behavior, but neither is hauling ass to ollie a table in front of the people who make your shoes.

VP: Has anyone ever felt insulted that you are taking the shoe they are working hard to manufacture and purposely wrecking them?

J: The typical response is simple amazement. In my experience, our factories are so proud of what they are making and how they’re being used. At the end of the day, skateboarding shoes tend to be very 'youthful' in that they use all kinds of colors/materials and are constantly evolving. Prior to social media, the factory wouldn’t see how their shoes were being presented to the world of skateboarding, just because the reach of skateboarding advertising was in a 411 or skate-specific print.

VP: How did you go from designing titles for crew videos to designing skateboard shoes?

J: I went to a two-year trade school that focused on multimedia design, which was basically what I had been doing with my friends. Filming videos, editing videos, and then creating a platform for the videos. I learned how to use all sorts of software that doesn’t even exist anymore. Towards the end of my program, I created a website called calumonn.com. It was a skate website that my friends and I developed, ran, and contributed to. At the time I lived with a filmer named Eric Trout and he would just film everyone that came through the apartment. It was great because we had endless content and always had new faces in the mix.

While we were making all this useless content, our roommate’s brother was working as a senior designer at Vans and was looking for an intern. Now, this is where I got really lucky. Most of the time, when Vans seeks interns, it recruits from universities. They’re usually looking at a pool of design students learning industrial design. Now, Jon (Warren), the guy that hired me at Vans, had seen a few talented designers hired without any cultural connection to skateboarding. That's how I was able to make it through the intern interview process, through my love of everything skateboarding. He saw I was interested in designing skate-related content for absolutely no other reason than I loved to do it. Fortunately, I had learned all the programs and am highly proficient on a computer, I’m not sure how far I would have made it without that. He took a chance on me, and it was probably a hard sell to his boss, but it really opened the door for me. Vans was my college of footwear design.

The Van Eslito Quattro, a John Cardiel pro model and a shoe Jeff had a hand in designing early in his career while at Vans.

VP: When was this?

J: I graduated high school in 2004 and moved to California that summer. I got the internship at Vans in 2006 and I was there for three and a half years until 2009.

VP: Did you overlap with Village Psychic interview alumn Neal Shoemaker at Vans?

J: Yeah! Neal was hired for a core skate position while I was an intern. I kept extending my internship because I wasn't sure if I wanted to work full-time yet. By the time I was willing to take a full-time role, the only position open was in the girls’ division—which was cool because I really wanted to learn how to design outside of skateboarding as well. I knew I'd eventually want to get back to skate specific design, but it's something I wanted to try. So, yeah, Neal and I crossed-over for about two years. He's still someone that when I see him, I want to take notes. He's got it figured out.

The Vans 44 High, Jeff’s first actual shoe design at Vans.

VP: How did you then move from designing at Vans to designing for Lakai?

J: I was getting flow from Girl and FourStar at the time through a guy named Jason Calloway who was the brand manager for FourStar. So in a way, the act of skateboarding is what actually got me in the door at Lakai. This was when Lakai was being transferred from Podium, and Girl bought the rights to Lakai, so it was coming over to the Crailtap building.

As that was happening, Lakai was looking for another designer to come in under Scott [Johnston]. It was so exciting to me because that meant I was going to get my chance to focus on skateboard-specific design again. Everyone I worked with in girls’ footwear over at Vans was really amazing--it was a real fun and diverse crew. I had a solid boss at the time too – thanks Pozzebon. But at 24 years old, skateboarding still occupied 100% of my thoughts and passion, so I had to get back into it.

The Lakai Griffin, on of Jeff’s shoe designs while at Lakai.

VP: Other than the obvious answer of being able to work under the Crailtap umbrella, and call Scott Johnston "boss", what excited you about the prospect of designing shoes for Lakai?

J: Vans made a lot of technical stuff in the 90's, but then the vulcanized-trend came in super-hot in the early-2000's, so companies weren’t creating very many new cupsoles in general. At that time, I was really interested in learning to design more intricate rubber and foam molds. I took four years of CAD [ autoCAD ] in high school, so I was very lucky to learn these engineering basics early on; so I had this engineering backbone that wasn't a post-grad approach but more of a base level of interest or understanding.

At Lakai, they were more known for designing and producing technical footwear. I saw moving over to Lakai as a huge opportunity to be able to work on that type of technical design.

Sketches from Jeff’s time at Lakai.

VP: What was it like being interviewed for a job by Scott Johnston?

J: It was interesting for sure. He stayed late at the Girl offices to do the interview. Scott is truly one of the nicest, warmest people. He had a real casual demeanor for the interview, which didn’t make it too intimidating. Scott is super clean-cut and I was just a dirty skate-rat at the time, so he probably took a look at me and thought, "Nah, not this dude." [Laughs] I showed up in some skated Half Cabs and torn black chinos, while Scott has some crisp Stussy collared shirt.

The interview started and it felt like we were already friends. I showed him a lot of the drawings and product I was working on. I may not have brought my A-game in regards to the drawings that I presented for the interview, but I’d like to think after he hired me, I was able to show I had a certain level of competence and skill.

VP: What was Scott looking for in someone to help him out at Lakai?

J: The goal was to bring someone in to take the in-line stuff of off Scott so he could focus on new models and longer-term planning. At the beginning, we'd simply split the workload down the middle, but then when it came to new projects like Guy [Mariano]'s shoe, he would take the lead. After a few seasons of working together, we started sharing those new projects more and more.

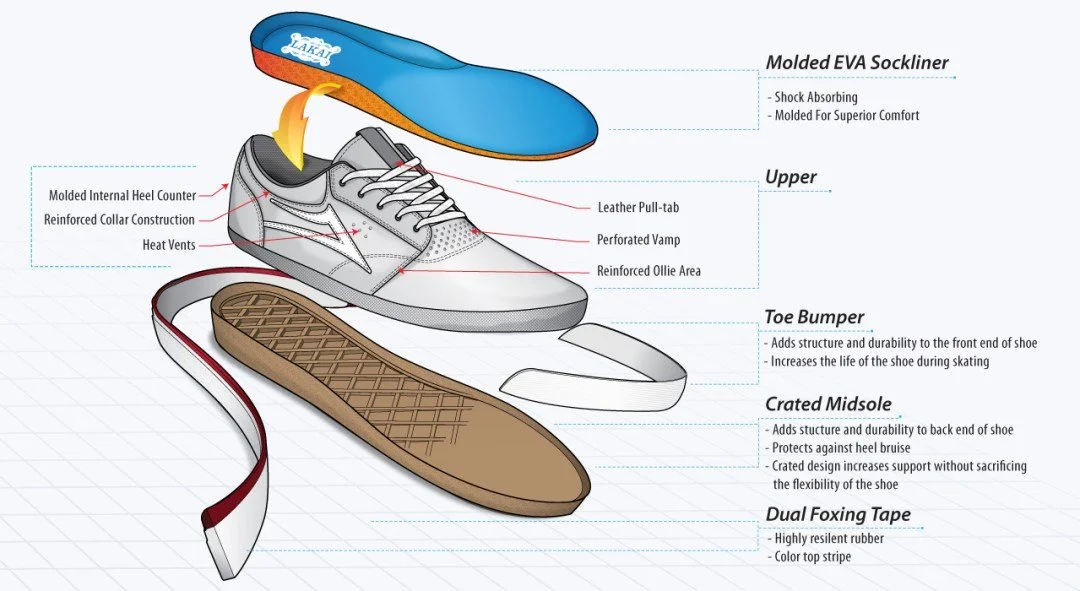

A breakdown of Jeff’s design for the Griffin.

VP: What was the first Lakai shoe that was all 'you' then?

J: The first shoe I did for them was called the Linden, and it was going to be Mike Mo's shoe. When he first came in to see the shoe he was super stoked on it and I thought, "This shoe is going to be a hit. This is going to be great." And then, later that week, Mike [Carroll] and Rick [Howard] came in and told us that Mike Mo was leaving. They told us about his offer from DC.

Because the shoe was so far along, Mike and Rick had a conversation with Mike Mo about keeping the shoe and releasing it without his name, which of course he didn’t care about since he was leaving the brand anyways. That was my first project with the brand.

The next shoe I designed was The Griffin. It was a simple lace-up vulc to share space with the Vans Chukka and the Janoski. That shoe was really interesting to design because it utilized a new last (the form of the foot that the shoe is built around) and the brand hadn’t developed a new last in a couple of years. Any time you suggest changing the 'fit' of the brand, there's a lot of red-flags that go up, and you have to convince everyone to devote the resources.

The design process for The Griffin was super cool because Scott and I were both designing different uppers and different tapes, but he let me design the sole all the way through. I think it was the first time Scott said, "Jeff, you've got this one" and it was really cool and empowering. I mean, he was my boss and could have just said, "We're going with my design", but he didn't. It shows Scott's character and how good he was at looking at the bigger picture. Scott helped me realize that you’re not designing the shoes for yourself, you're designing them for the person/pro whose shoe it is.

Another breakdown for one of Jeff’s projects, this time for the Fremont.

VP: And what about working out of the Girl building? What was it like having Mike and Rick as bosses? Were there times where you had to pinch yourself to realize it wasn't a dream?

J: All the time. Especially the lunch breaks. It wasn't until the Girl building-era was over that I realized just how special it was. I think of it this way – Mike and Rick don't put out a ton of footage and they aren’t active on social media, so having those moments of playing SKATE in the warehouse with them and seeing Rick do a nollie backside flip switch manual, it was just like ‘What the fuck?”

But maybe the main time that I really went "third-person" and thought to myself "How did I get here" was when we were at a tradeshow in Las Vegas, and I was walking with Scott, Rick, and Mike to the hotel and I had no idea how or why I was the fourth-person in the group. [Laughs]. It was just so odd to me.

VP: What was your state-of-mind when you heard that Scott was leaving Lakai and you were going to be the only designer at Lakai?

J: I was a little worried for two reasons: my wife was pregnant and the reality of losing a mentor. Scott was really great on his way out and put me at ease by telling me "Hey man, you've been ready to run this for a couple of years. In order for you to grow, I need to leave". I was like "Awww. Thanks Scott, but that's some bull shit" [Laughs].

VP: Did Scott leaving for Adidas plant a seed in your brain that you may be able to design outside of skateboarding someday? It seems like he was one of the first "core" designers to make a seamless transition into working for a corporate brand.

J: It wasn't the first time I had seen someone leave for a bigger brand, but for Scott it was a big deal because he was leaving his comfort zone by leaving Lakai. For me, I was just overwhelmed by both having a child soon and at the same time taking on all of the design for Lakai. Then shortly after, HUF invested in Lakai and the design-headquarters ended up in Downtown Los Angeles, which meant I had to work farther away from my wife and newborn. So it was a really crazy time for me.

The finished version of the Fremont.

VP: What are some of the projects you worked on after Scott left?

J: I think the Fremont was the first project to come out once we were up in LA working within HUF. The concept was to make a modern-day tech shoe that maintained a slim profile and was comfortable all day. It was fun to design because it had a bit more complexity than some previous models.

I worked with Marc Johnson on trying to take a prior shoe called the Echelon, which was a dress-shoe looking cupsole, and making it into a modern vulc shoe. It was looking really good, and I was really excited about it, but it didn’t go anywhere.

VP: How did you transition from Lakai over to New Balance?

J: There really was no reason to leave Lakai.

The thing is, I went from a roughly 15-30 minute commute to an hour-and-a-half to two hour commute during the first year of my daughter's life. That put a lot of pressure on my wife, especially because we don't have any family here.

I had a lot of good times. We had a bar on the first floor of the building and we were working side-by-side with everyone at HUF, so it was really easy to be late getting home. That's not saying I was there late every night or anything, but it made it easy to "wait for traffic to die down". My wife and I started considering whether we should move from Long Beach and then, randomly, I got a text message from Jason Rothmeyer on my birthday, saying "Hey, Jeff. I don't know if you're looking for anything, but we [New Balance Numeric] just lost our designer and we're going to be looking for one soon. You should throw your name in the hat."

VP: Whoa. Good timing.

J: It was just so coincidental because I had just finished a portfolio website I had been working on months before. I sent Rothmeyer the link and got an interview. It was the most intense interview process I've ever gone through. Even at Vans, where the process was sort of rigorous,that was just for an internship, whereas this was an interview at New Balance, and it was for a proper position. I was interviewing to be the only designer for this category that New Balance wanted to grow.

Jeff’s work brought him to New Balance Numeric. New Balance Numeric 508.

VP: When was this interview in the New Balance Numeric timeline? Is this post-Black Box?

J: Yes. Post Black Box by about a year, maybe less. The designer before me, Kelly Kikuta, put in a lot of solid groundwork for me to build from. He had just finished the 868 as I was coming in. It was cool to see the range from their vulc shoes to the 868--which is the most technical shoe New Balance had at the time.

It was amazing to see the input from a resource level into that shoe. New midsole tech (N2), lab-tested muti-density foam toolings, and strategic reinforcements both external and internal on the upper. A lot of thought went into that project, and it was inspiring to be joining with that shoe already in the mix.

VP: So, when you moved over to New Balance, what was the general atmosphere?

J: I definitely felt that in skateboarding, New Balance couldn't afford to have any more of those hiccups. I saw it at Lakai a couple times when we switched factories and an entire run of shoes might not come out as well as expected.

I think it was Kelly Bird that told me in shoe production it takes five rights to correct a wrong. For example, if you're a kid and you buy a pair of shoes for $60 or $70 and they fall apart, you're not going to go buy them again – it takes time for that interest to come back or a new compelling model that has visual quality. Luckily, before I got to New Balance, they had already gotten the behind-the-scenes stuff back on track and it was ready to move forward. One of the first tasks was to get the vulc line back on track.

VP: How'd you go about doing that?

J: It took traveling as a group to the factory in order to explain how vigorously the shoes were going to be used. We kept having issues with the vulcanized tape delaming from the upper. For a standard vulc shoe, most factories will do a 'flex test' where they have a machine flex the shoe over 180,0000 times to simulate the average life of the shoe. The goal is to see no visual signs of wear or delamination after the test.

We also started a new wear test program where we have a select few people skate new shoes--or even existing shoes, but with new materials. It really allows us to vette out issues before they end up on shelves.

This is the New Balance 440, a cupsole designed by Jeff to convert the vulc sole inclined.

VP: What about from the design side, what needed work?

J: When I first started, I was looking at all the classic New Balance shoes and it was really daunting. There was just so much. In skateboarding, simplicity is oftentimes the key to a successful skate shoe. So, I was trying to figure out how to bring New Balance and its technology into that realm of simplicity in design.

The design team recognized we had a couple good vulcs, but they really wanted us to create a solid cupsole. My first full design project (upper, outsole, midsole, and tread pattern) was the 440. The concept for the 440 was to make a cupsole shoe that transitions people out of vulcanized and into a cup. We wanted it to be a timeless New Balance classic that never existed. It was a tricky goal, but it's become one of our best sellers next to the Foy and the Tiago. It came out in summer of 2018.

The shoe has double suede in the toe area. A lot of brands will skip that part and just join the toe to the vamp ( vamp is the toe area of the shoe)--but just do a couple kickflips and that thing will open right up. We actually glued the toe cap down so that thing doesn’t go anywhere. The cupsole portion was designed to feel like a vulc up front with plenty of support in the heel.

We used a New Balance legacy tech called "C Cap" which is New Balance's tried and true EVA foam. We could have used some fancier technology, but every time you do that, you bring the price up. We really wanted to keep the price 'down' to keep it accessible. It ended up being a $75 shoe, but to me, it's worth every penny. It's one of my favorite shoes I've ever worked on.

VP: It doesn't hurt that Tom Knox has been anchored to the 440.

J: That helps so much! You see him skate in the 440 and you're like "Oh, that looks like a damn fine shoe." Tom's style and finesse on a skateboard is exactly the lane you wish to sit in. He can make anything look good.

The first sample of the New Balance 1010, the Tiago Lemos pro model.

VP: How's it differ designing an understated cupsole for someone like Tom Knox, to a hyper technical cupsole for someone like Tiago?

J: One of the things we were missing at the time was a chunky, or more traditional, skate shoe. When we started talking about it, we tried to design as if New Balance was making skate shoes back in the late 90s early 00s. We pulled a whole board together of skate shoes that we all liked from that era and then pulled a bunch of New Balance shoes that also came out within a five-year window of that timeframe as well.

The tricky part was then trying to take those late 90s designs and make them more contemporary. I mean, we didn’t want to just remake a Lakai Staple or the éS Koston 2. If you tried to skate any of those shoes in the same proportions now, you would be like, "Nah, I can’t skate that".

The 1010 as a finished product.

VP: So, where else did you look for inspiration?

J: We went over to the basketball design/research team and asked what type of foam technology and rubber compounds were working for them. They were using this foam tech called Fuel Cell and seeing great results.

We were really looking for something with a higher rebound than your average skate shoe. We used a foam in the forefoot that will help propel your foot forward when you push off and then chose a firmer material for the heel to absorb impact. Once we decided on the tech of the shoe, the hard part was coming up with a suitable upper. The final and hardest part was then figuring out the design of the sole. We didn’t want to just put on a flat sole, so we knew we had to do something new and unique.

One of the rules we decided to give ourselves was that the shoe couldn't have any straight lines (besides the N logo). I knew I could throw whatever I had at it, and the challenge became designing something new that looked like it was rooted in the brand's history.

VP: Where did Tiago come into the design picture?

J: Well, we had what we thought was going to be the final sample and we had the sample brought down to Brazil to Tiago during Street League. Reportedly, when Tiago took a look at them, he said, "This is the shoe I've always wanted, but could never get." Or something along those lines. Obviously, that was incredibly flattering considering the shoe was designed with a skater like him in mind.

VP: What's something you can point to on the 1010 that Tiago had a hand in designing?

J: He actually took something off. There's a triple stitch across the toe and we originally had the third stitch going straight across rather than up into the eye row. It was designed to create an anchor point in case you ripped the toe cap. He reduced the tongue foam by 5mm, helped us perfect the internal heel lock system and improved the internal backers in key areas. His final touch--it was so micro, but I love it -- was to increase the laces by 2mm of thickness. I'm telling you, in shoe design, it's the subtleties.

The New Balance 913, Brandon Westgate’s first pro model with the brand.

VP: What about the new Westgate shoe? How'd that come together?

J: The 913, his first shoe, was designed as a slim technical skate shoe that would utilize some of the 868 tech. But, again, whenever you add a bunch of tech to a shoe, the price always rises with it.

When we first started working on that shoe, I told Brandon that the shoe is probably going to cost around $100, and his response was "How the fuck are kids going to afford this?" Him saying that made us realize his second project will have to be much more price conscious. So, we decided to make something for him that would be more accessible for skaters. To keep the costs manageable, we took an existing sole from the 288 and designed an upper that pulled details from the 913 and C600 (a cycling shoe designed in the Tokyo design studio). We worked on screen to get the ideal pattern/details, had Brandon test multiple sample rounds and got it just right.

Jeff doing what he does best (besides skating) with recent VP interviewee Tom Karangelov. Photo by Jake Darwen.

VP: From the outside perspective, it seems like the slow burn of the New Balance skate program has really gained traction over the last couple of years, what's the secret?

J: We're really lucky New Balance took the approach of giving the skate program a satellite office and allowing us to essentially operate on our own with support of their infrastructure. The hardest part was just gaining acceptance of the brand in skate culture, and there's probably still a ways to go there, but I think New Balance has brought a lot of integrity to the design and manufacturing of the shoes and to the skaters it's brought to its team. We’re really just trying to stay in our own space.